When a public space has purpose and meaning for its community, it becomes a place. Places, like this one in Mumbai, can drive the social and economic value of a community. | Photo by PPS

At the Urban Age Conference in Delhi last November, head of UN-Habitat Joan Clos stressed the need for a new paradigm for shaping communities around the world, whether in rural areas or urban centers. When asked if that meant that government(s) would need to change as well, Dr. Clos replied with a brief and direct “yes,” before returning to his seat.

At PPS, we recognize the urgency of this call. We are also deeply aware of the challenges facing our cities—challenges that have in many ways been intensified by today’s unprecedented rates of urbanization such as social segregation, traffic congestion, inequity, unplanned sprawl, and environmental degradation. But even despite these global pressures, cities also contain unique tools and opportunities for confronting these issues—they have long been sites of great social transformation and democratic action, and they continue to be powerful engines of economic growth and innovation. To harness these opportunities, though, as Dr. Joan Clos has argued, “requires a shift in mindset away from seeing urbanization as a problem. Instead, we need to approach urbanization as a solution.”

To begin thinking differently about the ways we create, plan, and experience urban life, governments at all levels must recognize the formation of public spaces and places as the core incremental process of city-making. What is more, given its power to achieve multiple outcomes quickly, effectively, and democratically, Placemaking and place-led governance (putting “place” at the center of policy and planning frameworks) need to be fundamental components in this new urban agenda.

With all this talk about “public space” and “place,” though, is there really much difference between the two concepts? This is a discussion that is very important to our work here at PPS, and the ever-evolving debate is one that goes well beyond semantics. So what is the distinction between these concepts, and why does it matter?

We’re glad you asked.

Simply having a public space often isn’t enough, as was the case at this site in Gyrumi, Armenia. After a three-day festival of art, food, and experimentation by PPS, the space became a true place. | Photos by PPS

RETHINKING PUBLIC SPACE OR WHEN DOES A SPACE BECOME A PLACE?

Everyone has the right to live in a great place. More importantly, everyone has the right to contribute to making the place where they already live great.” – Fred Kent

Let’s start with Public Space. Outlining the role and value of public space has long been a subject of academic, political, and professional debate. At the most basic level public space can be defined as publicly owned land that, in theory, is open and accessible to all members of a given community—regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, age, or socio-economic level.

Access to adequate public space and basic services is an essential human right, and ensuring the availability of these resources in developing and newly urbanizing countries where they are lacking is of paramount importance: Setting aside and protecting public space, as NYU’s Paul Romer has urged, should be the “number one priority” for city leaders to make life better for its residents. Where open public space already exists, however, their thoughtful design and maintenance is vital for the health—cultural, social, economic, and physical—of any city.

In Juchitan, Oaxaca, the city hall is on top of a public market on a public square. Everyone is working to maximize public life and the Placemaking benefits of public space. | Photo by PPS

Places, on the other hand, are environments in which people have invested meaning over time. A place has its own history—a unique cultural and social identity that is defined by the way it is used and the people who use it. It is not necessarily through public space, then, but through the creation of places that the physical, social, environmental, and economic health of urban and rural communities can be nurtured.

In everyday language as well as in existing literature and policy documents, the distinction between “public space” and “place” is a slippery one. The terms are sometimes even used interchangeably, as in the following definition of “public space” found in the 2013 Charter of Public Space—an important reference guide that was adopted in 2014 by UN-Habitat:

Public spaces are key elements of individual and social well-being, the places of a community’s collective life, expressions of the diversity of their common natural and cultural richness and a foundation of their identity.”

However, not all public spaces are effective places. Dangerous or impassable roads, abandoned lots, or poorly maintained transport stations or parks that are unsafe for women and girls are indeed “public spaces,” but they surely do not contribute to the “well-being,” “collectivity,” or “cultural richness” of cities or communities. Quite the contrary, in fact. Poorly managed or inaccessible public spaces can actually create barriers between people and places—they can be unsafe, exclusive, or otherwise threatening on a variety of scales.

The detailed Charter wrestles with the distinction between these intimately related terms rhetorically, but not conceptually—at one point even stating that “the objective is that all public spaces should become places.”

Great! That’s our goal too! But without acknowledging the human-led activity of Placemaking—the process by which a physical environment is made meaningful, or by which a public space becomes a place—the transition from point A to point B seems muddled. Without acknowledging the subtle but crucial distinctions between these types of spaces, we can overlook the ways a place-based approach to planning and governance can generate solutions for multiple problems at once—with greater results and fewer costs.

For this reason, we need to continually revisit the language that is being used to describe the terms and significance of “public space.” In order to move these very important conversations in the direction of immediate implementation and change, we must be sure to clearly connect these issues with the idea of “place”—not as an inert object or amenity bestowed onto people by experts or leaders, but as the framework for a system-wide process that empowers citizens to shape their city at many levels.

Introducing active terms like “Placemaking” into critical discourses and documents (along with actionable tools for its implementation) will go a long way in directing focus towards active solutions that can have tremendous impacts on communities around the world.

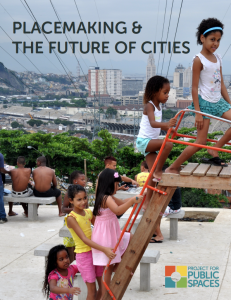

THE PLACEMAKING MOVEMENT

More and more people and communities around the world are beginning to recognize, and to fight for, the power of place in transforming cities and the everyday lives of their residents. From Detroit to Durban, from Adelaide to Sao Paulo, governments and citizens alike are finding that working together around the common goal of “place” is a key step in creating safer, healthier, and more inclusive communities.

The vast social media network of PPS offers another window into the momentum that is gathering around the Placemaking cause, and the Placemaking Leadership Council now includes over 800 members from 50 countries!

As World Urban Campaign’s Genie Birch has explained, our ultimate goal is to “achieve a world of shared prosperity, one where place matters.” Place does matter—it matters not only for sustainable urban development, but also for the health, safety, and happiness of every human being on the planet. For these and a thousand more reasons, we need to take our places seriously—the way we shape them, manage them, and live them together in the 21st century.

To echo Joan Clos’s call for a “New Urban Agenda,” we are indeed at a critical juncture for thinking about how to ensure the safety, sustainability, and resiliency of cities across the globe. Consider this sobering statistic: Since 2009, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities, and the number of urban dwellers is set to double in the next several decades. As we prepare together for an urban future, we must get to work now to create safe, accessible, and inclusive places that can sustain and nurture the world’s growing populations. A sustained focus on place and Placemaking can and should be the way forward in this new paradigm for change. In our project work in nearly 50 countries worldwide, PPS has found that that when you focus on place, you do everything differently.

To echo Joan Clos’s call for a “New Urban Agenda,” we are indeed at a critical juncture for thinking about how to ensure the safety, sustainability, and resiliency of cities across the globe. Consider this sobering statistic: Since 2009, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities, and the number of urban dwellers is set to double in the next several decades. As we prepare together for an urban future, we must get to work now to create safe, accessible, and inclusive places that can sustain and nurture the world’s growing populations. A sustained focus on place and Placemaking can and should be the way forward in this new paradigm for change. In our project work in nearly 50 countries worldwide, PPS has found that that when you focus on place, you do everything differently.

Source: www.pps.org